Professor Mann’s climate comeback: urgency, action, and hope

Professor Michael E. Mann, Presidential Distinguished Professor in the Department of Earth and Environmental Science at the University of Pennsylvania, also serves as Vice Provost for Climate Science, Policy and Action, and Director of the Penn Center for Science, Sustainability, and the Media.

Professor Mann’s research focuses on the Earth’s climate system along with the science, impact and policy implications of human-driven climate change. He was a Lead Author for the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in 2001 and, together with fellow IPCC authors, contributed to IPCC’s Nobel Peace Prize in 2007. He also chaired the organising committee for the National Academy of Sciences “Frontiers of Science” in 2003.

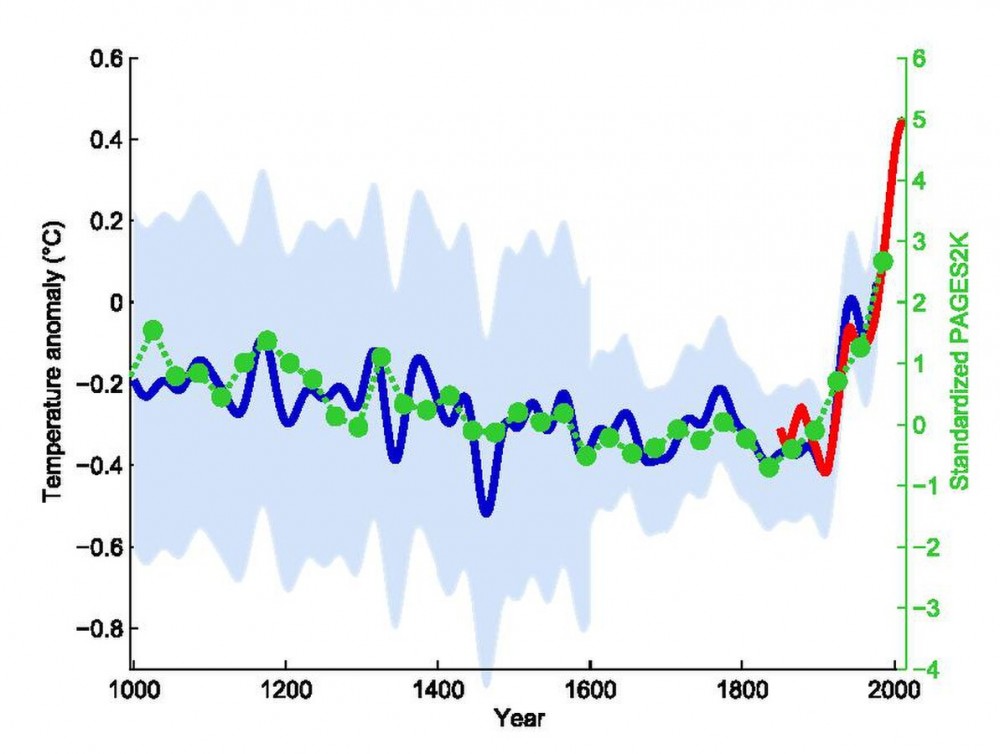

Professor Mann is best known for developing the “hockey stick” graph, which illustrates the rapid increase in global temperatures over the past century. His extensive publications centre on the causes and impacts of climate change. He advocates for climate action across television appearances, newspaper articles, public talks and popular books. His research has made significant contribution to understanding historical climate patterns and emphasises the urgency to mitigate climate change.

Professor Mann was awarded an honorary doctorate by EdUHK in September 2025 in recognition of his exceptional contribution to the field. He delivered a talk titled “Urgency and Agency in Addressing the Climate Crisis” on 26 September, upon receiving the honour. In the lecture, Professor Mann presented the latest climate science findings, voiced his opposition to misinformation, and shared advice on effective communication around climate change.

The distinguished lecture, organised by the Department of Science and Environmental Studies (SES), brought together students, faculty, and members of the EdUHK community for a discussion on climate challenges and the importance of joint and individual action. EdUHK President Professor John Lee Chi-Kin gave opening remarks for the lecture. Among other guests present were EdUHK Council Chairman Dr David Wong Yau-kar, Dr Tom Fong Wing-ho, Vice President (Administration) and Secretary to Council, and Mrs Mann.

The lecture was followed by a Q&A session moderated by Professor Li Wai-keung, Dean of FLASS, and Professor Keith Ho Wing-kei, Head of SES. Below is a summary of Professor Mann’s lecture and the Q&A session, with sub-headers added for clarity.

An internal ExxonMobil report published in 1982 predicted that catastrophic events would occur if humanity continued to burn fossil fuels and failed to take rapid action on climate change. ExxonMobil didn’t take the necessary steps, but instead hid the report and tried to convince the public that climate scientists were mistaken.

Today, these dire predictions are coming true. In 2024, Hurricane Milton hit Florida as a Category 5 storm by the American meteorological system, and was described as potentially catastrophic by the media. While I visit Hong Kong for this event, the city narrowly escaped disaster from Typhoon Ragasa, this year’s most powerful storm.

Because of the lack of action, powerful hurricanes, superstorms, floods, wildfires, heatwaves, and droughts are occurring at unprecedented levels around the globe. Science predicted this would happen. Physics shows that the quality of moisture the atmosphere can hold is an exponential function of temperature. As the planet warms, atmospheric moisture increases, fuelling more intense hurricanes and causing heavy rain.

To limit global warming to 1.5°C by the end of the 21st century, we must control carbon dioxide emissions. The cost of inaction is high; every delay means we will need to take even more drastic measures, and urgently.

Despite overwhelming evidence, climate contrarians or deniers continue to express doubt about the climate change consensus. Some claim climate change is a fictional problem. In truth, events have gone beyond our predictions and more extreme weather is taking place.

A paper, titled “Increased Frequency of Planetary Wave Resonance Events Over the Past Half-Century”, which I worked on, found that traditional climate models do not factor in the impact of jet streams. As current models do not adequately account for jet stream effects, climate scientists may be underestimating the crisis.

Some opponents argue that the world is warming faster than expected and claim that it is already too late to act. This sense of doom and despair can lead to disengagement and is just as unhelpful. Although some consequences of climate change are exceeding predictions and current models have underestimated sea-level rise and ice-sheet collapse, the world’s temperature is rising as exactly predicted under the business-as-usual scenario. The reality is severe enough to call for immediate action. There is no need to exaggerate the facts to provoke urgency.

Despite the severity of the crisis, there are reasons to be hopeful. Scientists once believed that the long lifetime of atmospheric CO2, combined with the thermal properties of the oceans, would cause global temperatures to keep rising for 30 to 40 more years after the world reached net-zero-emissions. However, recent climate models suggest that the Earth will stop warming almost immediately once we cease carbon dioxide emissions. This is because the carbon “sinks”, such as oceans and the biosphere, will absorb atmospheric CO2, offsetting the warming effect due to the ocean’s thermal inertia.

Although we already have the technology needed to combat climate change, misinformation and fake news across social media jeopardise our ability to respond effectively. Whether it is outright denial of the climate crisis or a doomsday sentiment, both undermine constructive discussions and weaken efforts to mobilise public support for necessary solutions.

As the largest manufacturer of solar panels and related technologies, China is exporting solar technology to other countries and helping drive the global transition to clean energy sources.

The fact is if every country adheres to its net-zero CO2 emission commitments made at COP26 in 2021, global warming can be kept below 2°C by 2100. There is also positive news from China, which, as the world’s largest greenhouse gas emitter, is making real progress reversing emissions trends by shifting from fossil fuels to renewables. The Chinese government has invested heavily in renewable energy technologies, such as wind and solar power, stimulating more innovations and leading to efficiency improvements. As the largest manufacturer of solar panels and related technologies, China is exporting solar technology to other countries and helping drive the global transition to clean energy sources.

The United States, as the largest cumulative carbon emitter, also has a vital role to play. As a petrostate, its public policy is heavily influenced by the fossil fuel industry. I must stress that although science provides the necessary technology, it faces constant attacks from fake news and misinformation. Vested interests use multiple strategies—distraction, division, and fearmongering—to delay the decarbonisation of the US economy. These sentiments put our ability to address the challenge at risk. Fortunately, China brings a hope with ambitious climate goals. The growth of its solar power and EV industries is helping to level off emissions. China is providing much-needed leadership in the global struggle against climate crisis.

Students can be change-makers in this fight. We must instill not just urgency but also a sense of agency.

We face immense challenges from climate change, including the real risk of deadlier pandemics linked to environmental degradation. Yet, the greatest obstacle is misinformation, which paralyses our response. I always emphasise that the antidote to doom is action. Many students I speak with fall into doomsday thinking, feeling it is already too late to respond to the existential threats we face.

Education is critical to fighting this sense of hopelessness. We need to give the next generation an accurate understanding. As educators, I believe students can be change-makers in this fight. We must instill not just urgency but also a sense of agency. Without action, we could lose natural wonders such as the Great Barrier Reef and polar bears. It is never too late to act; we must start now if we want a thriving planet for the future.

Everyone has a voice when it comes to addressing climate change. We can make our voices louder through social media and by sharing ideas with friends and colleagues. Working with influential figures can extend our reach even further. We should use whatever strengths and talents we possess to advocate for immediate action and show that it is never too late to make a difference. Together, we can make the call for climate action go viral. Collectively, we can create a movement to fight the climate crisis and safeguard our planet.

Professor Ho: How can we start a meaningful conversation to help people see the urgency of tackling climate change?

While polls indicate only around 10% of Americans are opposed to climate advocacy, public perception is that it is closer to 30%.

Professor Mann: There is a coordinated misinformation campaign that distorts public understanding of climate change. While polls indicate only around 10% of Americans are opposed to climate advocacy, public perception is that it is closer to 30%. This misconception feeds a myth of widespread opposition, discouraging people from discussing climate science if they believe most others dismiss it.

Instead of investing effort in persuading this minority, we should focus on the uncommitted middle—those who lack a clear understanding but are open to discussion. Engaging with this group can lead to more productive conversations, and promote action.

Professor Mann: Climate scientists use two types of models to understand and predict events: statistical modelling and physical (or dynamic) modelling. Statistical models use historical data to forecast things like hurricane frequency; physical models use the laws of physics to simulate climate processes and predict future events.

The famous British statistician George Box once remarked, “All models are wrong. Some models are useful,” pointing to the limitations especially of statistical models. Nevertheless, whenever these models, statistical or physical, have gone wrong, they tend to underestimate the impacts of climate change, including those about sea-level rise and ice-sheet melting.

Professor Ho: Climate change affects every nation but not every nation contributes equally to climate crisis. In view of this, what is a fair global solution?

Professor Mann: Climate change brings a profound ethical dimension.

It is unjust that those who have contributed least are often hit the hardest. Individuals in developing countries usually have carbon footprints hundreds of times lower than those in wealthy Western nations, yet suffer far more from issues like food insecurity or health crises because they have fewer resources to adapt. We must reframe the climate issue, recognising its ethical challenge.

Professor Li: What role do individuals play?

Professor Mann: People can contribute by using less plastic and supporting recycling. However, to truly win, we need government policy and systemic change at the root of the climate crisis. Fossil fuel companies often resist necessary policy change and redirect the conversation to focus on individual behaviour, ignoring their own responsibility for the crisis.

This focus on individual behavioural change can undermine the push for systemic change. While sustainable personal habits are important, it is equally important for individuals to press governments to take large-scale action.

Professor Ho: Have there been recent success stories?

Professor Mann: China is a strong example of climate action. Unlike the United States, which has a legacy of two centuries of fossil fuel burning and carbon dioxide emissions, China is making substantial efforts to combat the crisis. The rapid growth of its electric vehicle industry and improvements in solar technology are making a difference globally.

China is nearing its peak carbon emissions and is ahead of its international commitments, showing true leadership in tackling climate change.

Professor Ho: What have motivated you to persist throughout the climate cause regardless of all the difficulties?

Moments like today’s lecture show me how passionately students care about making a difference.

Professor Mann: Social media is often filled with negativity and arguments, which encourages a pessimistic view of humanity. Consuming such distressing news can amplify despair. It makes us lose sight of the potential for change.

In contrast, engaging with real people—educators, researchers, and students—is inspiring. Moments like today’s lecture show me how passionately students care about making a difference, renewing my motivation for this cause.

Professor Li: How should we measure our achievements in combating climate change?

Professor Mann: When measuring progress, we should not see it as a simple matter of success or failure. Setting limits like the 1.5°C threshold highlights the potential consequences of inaction but is not an all-or-nothing test. There are important tipping points, such as those that could collapse certain ocean currents or ice-sheets, but we are not poised on the edge of a cliff—we still have options and choices as we go.

Think of this journey as being on a highway. Even if you miss an exit, you can still take the next one. Every bit of carbon we keep out of the atmosphere brings a better future. We still have agency in this fight.

EdUHK Council Chairman Dr David Wong Yau-kar: I have one comment to share: Thirty or forty year ago, people saw environmental spending as a cost that is bad for the economy. It is encouraging that China took the view that the green industry can actually generate economic growth. I also have a question: The earth has a long climate cycle; how much climate change is caused by human activities, and how much it is part of a natural process?

Now we are releasing it again at an alarming rate in just a short space of time. If we continue down this path, the infrastructure supporting our current population will not be able to cope.

Professor Mann: In the US, critics say spending on fossil fuel industry is an investment, while money for green energy is labelled a cost. This view ignores the substantial social costs from fossil fuels. Studies show that fossil fuel consumption not only causes pollution and urban heat stress, but also leads to premature mortality. These are significant costs often ignored in business calculations.

My book “Our Fragile Moment” highlights that the conditions needed for human life are delicate. Though periods of climate variability have sometimes encouraged innovation, the climate window in which civilisation can thrive is very narrow.

A hundred million years ago during the mid-Cretaceous period, carbon dioxide levels were much higher than today. Over millions of years, nature gradually removed carbon from the air, storing it underground. Now we are releasing it again at an alarming rate in just a short space of time. If we continue down this path, the infrastructure supporting our current population will not be able to cope.

An audience: How to communicate effectively with different stakeholders on climate issues?

Professor Mann: I learnt a great deal from my late friend and mentor Stephen Schneider, who always said, “The truth is bad enough”. He was tireless in communicating the climate threat to the American public.

Schneider had three rules for good communication. First, he advised us to “know thy audience”, which involves understanding the perspectives and concerns of those we are addressing. Second, he emphasised the importance of “knowing thyself”—being authentic and genuine when communicating a message. Finally, he reminded us to “know thy stuff”. This means grasping the various dimensions of climate change, including not just the scientific facts, but also the social concerns, policy issues and etc.

Climate change touches every part of life, from the economy to health to ethics. By highlighting these connections, we can encourage more meaningful discussions and wider engagement.